In 1966, Bob Dylan was interviewed by Playboy. Over that past year or so he had been involved in a lot of controversy and acrimony over his embrace of rock music.The folk music scene viewed the move as nothing short of treasonous. Naturally, the interview touched on Dylan's view of folk music.

Songs like "Which Side Are You On?" and "I Love You, Porgy" - they're not folk-music songs; they're political songs. They're already dead. Obviously, death is not very universally accepted."

Don't get me wrong, I think that Which Side Are You On is a brilliant song, and in my opinion, one of the finest examples of political/propaganda songs ever written. However, it is lacking a certain timeless quality, and it is this quality that Dylan found in what he termed traditional music.

There's nobody that's going to kill traditional music. All these songs about roses growing out of people's brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels - they're not going to die."

The music packs an emotional punch because it is

[T]oo unreal to die. It doesn't need to be protected. Nobody's going to hurt it. In that music is the only true, valid death you can feel today off a record player."

Dylan called it "plain simple mystery," and identified another significant aspect of the music's timelessness- myth.

It comes about from legends, Bibles, plagues, and it revolves around vegetables and death.[1]

In a earlier interview, Dylan expanded on this mythic aspect of folk/traditional music.

There is--and I'm sure nobody realizes this, all the authorities who write about what it is and what it should be, when they say keep things simple, they should be easily understood--folk music is the only music where it isn't simple. It's never been simple. It's weird, man, full of legend, myth, Bible and ghosts. I've never written anything hard to understand, not in my head anyway, and nothing as far out as some of the old songs. They were out of sight.[2]

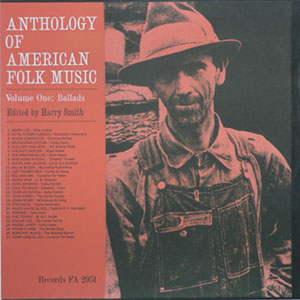

One of the more influential sources for this sort of music was Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music. When the Anthology was re-released in the mid-1960s, the cover depicted a Depression-era labourer. This fit perfectly with the public perception of folk music as the advocate of social justice, but it misses what Smith was doing. The original cover art was taken from a work by the 17th century esotericist, Robert Fludd. It showed the hand of God reaching out to tune a giant monochord thus harmonising the various spheres. The liner notes quote Alesteir Crowley and Rudolph Steiner, and the albums are in different colours each corresponding to a basic element as its organising principle! The tracks and their placement in the album contribute to the potent sense of mystery. The effect as a whole is alchemy, not social protest. There are songs on the Anthology dealing with harsh working conditions, but they are there because they help to tell a story. They command our attention not because they call us to action, but because the picture they paint is so compelling and vivid that we can't help but be drawn into it.

A classic song from the Anthology, My Name is John Johanna taps into this mythic undercurrent. It transcends the genre of hardship songs because it tells a very individual story without a grand, unifying theory of worker's right vs. labour exploitation behind it. The story's use of myth makes its characters larger than life, in the best traditions of Twain and Dickens. It feels much older than it really is. Songs preaching social justice can get very tedious. Not because there is anything wrong with striving for social justice (I think that we should all be striving for it), but because the message is heavy-handed. Art is subordinated to the message. The world created in John Johanna is not real, and it doesn't correlate to the world at large, but the imaginal effect is what means that it will never die, making its mix of the mundane and the mythic eminently relatable.

|

| Cain flying before Jehovah's Curse by Fernand Cormon |

The song opens very intimately with the narrator- John Johanna- giving his name and a little of his story. A migrant worker, he's been everywhere and seen everything, but then he came to Arkansas. In the song Arkansas is not so much a real place as it is the definition of misery, a stand-in for Hell.

John Johanna gets a train ticket, travels to Arkansas, and runs into a friend. While the friend, like the narrator, has an ordinary name- Alan Catcher- he is also known by a nickname: Cain. The nickname is ominous, and Alan Catcher's physical appearance matches it. He is like a walking skeleton, seven feet two inches in height, and his long hair hangs down in rat-tails. The description emphasises his otherworldly nature, though he is fully human. In Western culture, Cain was often depicted as a wild man, whose very appearance is cursed. In short, nothing good can come from associating with the namesake of the original outcast. Alan Catcher claims to run the best hotel in Arkansas, so John Johanna follows him home. The rates are exorbitant, the food is inedible, and starvation is pictured on Catcher's pitiful face. John Johanna plans to live early the next morning, but Alan Catcher talks him into staying and working for him. The same rate as board, and all the beef he can chew. He promises that John Johanna will be transformed into a different (presumably better) man before he leaves. The work is draining swampland, and after six weeks of it, John Johanna feels so thin that he can hide behind a straw. The imagery of swamp has undertones of Hell or Purgatory, such as Dante's portrayal of the Styx, but at any rate, it is entirely unfit for human dwelling. Instead of Paradise, he found the primordial ooze with only swamp rabbits for companions. John Johanna leaves- how he raised the money is never explained- and he is indeed a changed man, but not for the better. The nearest he is willing to approach Arkansas is through a telescope. It is on that surreal note of a telescope that can see from New York to Arkansas that the song ends.

My name is John Johanna, I come from Buffalo town,

For nine long years I've traveled this wide, wide world around.

Through ups and downs and miseries and some good days I've saw,

But I never knew what misery was, till I went to Arkansas.

I went up to the station the operator to spy,

Told him my situation and where I wanted to ride,

Said, "Hand me down five dollars, lad, a ticket you shall draw

That'll land you safe by railway in the state of Arkansas."

I rode up to the station, I chanced to meet a friend.

Alan Catcher was his name, although they called him Cain.

His hair hung down in rat-tails below his under-jaw,

He said he run the best hotel in the state of Arkansas.

I followed my companion to his respected place,

Saw pity and starvation was pictured on his face.

His bread was old corn dodgers, his beef I could not chaw,

He charged me fifty cents a day in the state of Arkansas.

I got up that next morning to catch that early train.

He says, "Don't be in a hurry, lad, I have some land to drain.

You'll get your fifty cents a day and all that you can chaw,

You'll find yourself a different lad when you leave old Arkansas."

I worked six weeks for the son-of-a-gun, Alan Catcher was his name.

He stood seven feet two inches, as tall as any crane.

I got so thin on sassafras tea I could hide behind a straw,

You bet I was a different lad when I left old Arkansas.

Farewell you old swamp rabbits, also you dodger pills,

Likewise you walking skeletons, you old sassafras hills.

If you ever see my face again, I'll hand you down my paw,

I'll be looking through a telescope from home to Arkansas.

[1]http://www.interferenza.com/bcs/interw/66-jan.htm

[2]http://www.interferenza.com/bcs/interw/65-aug.htm